What does the Cyber World have to do with hand crafted textiles?

Good question.

These days many people can’t live without technology. I admit I have become immersed in the technological world to the extent that I spend far too much time at a computer. And when it isn’t working I feel as if I have come down with a terrible illness. In November I had my Mac updated, because the Microsoft Office program I used threatened to close down if I did not update. This initiated a domino like series of mishaps and malfunctions. Incompatibilities. I use Microsoft Office for Mac- the manifestation of two titans jockeying for biggest and best.

This combo did not use to be a problem. But now I am shocked to see the polarization. When I decided I had to bite the bullet and purchase a new Mac, I asked the shop person, who until then had been very cheerful and attentive, if she would bundle Microsoft Office into the machine, as was done in my 2011 Mac. I received a chilly rebuff. “That is not our product,” she said. “You could go to a Microsoft store (miles away) or download the product.“

Ok, I thought. Sounds easy enough.

But trying to migrate my 2011 data to the 2017 Mac has been a nightmare. Two months after purchasing the Mac, and purchasing more than one version of Office, I am still struggling to make it work. I lost count of how many Microsoft techs I have talked to and chatted with, for hours and hours. And I’ve done the rounds with a few Apple techs as well. Neither will utter the name of the opponent- today one Apple person referred to “third party” products. By now more than weary, I had to make an effort to figure out that he meant “Microsoft Office.” But if a tech cannot solve the problem, he or she conveniently sends me to that “third party.”

I tried to check online to see if my problem is unique. I typed in “How many people use Microsoft Office for Mac?” I found ads for purchasing hardware and software. Finally, scrolling down, I found the article “Why I may never install Office for Mac again.” The world is too interconnected for polarization. We have to get over this phase fast. At some point, I wondered, if I have to choose between Apple and Microsoft, what would I decide?

At this point, I think neither.

The techs of both teams are remarkably similar. Well trained to say, “I understand…. I will solve your problem… I’m confident.” But I have talked to at least 30 people, none of whom solved the problem –nor followed through. Each one dropped the problem- hanging up in one way or another. What a terrible life! Never finishing anything, never connecting, never finding any satisfaction. Purgatory.

In the middle of all of this, I had the great privilege to have a conversation with William Bissell of Fabindia. He told me that he met with a group of women artisans and asked what they would like. They wanted four things, one of which was to finish whole products rather than do piece work. Closure, I feel, contributes a lot to satisfaction.

So these days I am way far from satisfied. But I am not giving up. A friend found an article online about an update (!) to enable updating from 2011 to 2016. Why did neither the Apple nor the Microsoft team know about this?? So that inched me toward resolution. Tomorrow I am going to take the situation in my own hands and simply wipe the new Mac clean and manually upload the files again.

Suddenly I remembered watching a National Geographic film on polar bears in Churchill, Canada with my Dad. One winter the bears were repeatedly coming too close to human civilization. The town called in expert scientists, who tried fantastically complicated solutions, trying to scare the bears with noises, recordings of other bears, and mechanical contraptions. Nothing worked. Finally a Native American resident of Churchill said quietly, “The bears are hungry.” He solved the problem by simply feeding them, far outside of town.

That story, and writing this down, have helped me feel a little better. The DE-humanization of increasingly, unnecessarily complex technology may explain why we care about human touch and cultural heritage.

“Simplify, simplify, simplify,” wrote Thoreau.

Once I get my damned computer up and running, I’m going back to the world of artisans and craft- human connection, the satisfaction of completion, slow and simple solutions. I can’t wait.

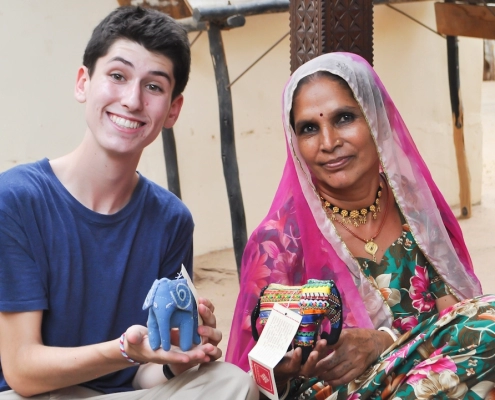

Hariyaben was one of the original trustees of Kala Raksha. I remember having a trustee meeting soon after we founded the organization. An elder man, a brother of her father-in-law, sat himself right in front of us to listen in. I was annoyed and told him that if he sat here, the women would not be free to speak as they have to cover their faces before elder men from their husbands’ families. He left. I felt triumphant. But Hariyaben refused to drink tea. It was some time later that I learned why. “You insulted my relative,” she said. From then I learned many things from her about art, artisans and culture.

Hariyaben was one of the original trustees of Kala Raksha. I remember having a trustee meeting soon after we founded the organization. An elder man, a brother of her father-in-law, sat himself right in front of us to listen in. I was annoyed and told him that if he sat here, the women would not be free to speak as they have to cover their faces before elder men from their husbands’ families. He left. I felt triumphant. But Hariyaben refused to drink tea. It was some time later that I learned why. “You insulted my relative,” she said. From then I learned many things from her about art, artisans and culture. After working on the exhibition for some time, she told me, “This idea of yours, this exhibition, is not new. We already have it. Every time a women is married she displays her dowry collection for her village– and then her husband’s- to see.

After working on the exhibition for some time, she told me, “This idea of yours, this exhibition, is not new. We already have it. Every time a women is married she displays her dowry collection for her village– and then her husband’s- to see.

Somaiya Kala Vidya was invited to begin a new Outreach project with a group of weavers in Varanasi. Like all collaborations, it involved negotiation. At first, the All India Artisans and Craftworkers Welfare Association (AIACA) wanted us to hold some workshops in Varanasi, followed by some workshops in Kutch. We said we would like to do the project as an Outreach project, as we have done in Bagalkot and Lucknow. Finally we settled on a jointly run project.

Somaiya Kala Vidya was invited to begin a new Outreach project with a group of weavers in Varanasi. Like all collaborations, it involved negotiation. At first, the All India Artisans and Craftworkers Welfare Association (AIACA) wanted us to hold some workshops in Varanasi, followed by some workshops in Kutch. We said we would like to do the project as an Outreach project, as we have done in Bagalkot and Lucknow. Finally we settled on a jointly run project.

“We want to weave!” They avowed, one after another, all nine of the Kamatgi Jeevadaara group. Remarkable for weavers in Karnataka today, when their community members refuse to give a daughter in marriage to a home with a loom. But in three and a half years, working artisan-to-artisan with Somaiya Kala Vidya graduates in our Bhujodi to Bagalkot Outreach project, these weavers have learned to love their tradition.

“We want to weave!” They avowed, one after another, all nine of the Kamatgi Jeevadaara group. Remarkable for weavers in Karnataka today, when their community members refuse to give a daughter in marriage to a home with a loom. But in three and a half years, working artisan-to-artisan with Somaiya Kala Vidya graduates in our Bhujodi to Bagalkot Outreach project, these weavers have learned to love their tradition.

Over twelve years of design education for artisans, the issue of copying has emerged among artisan designers. They discuss it furtively, angrily.

Over twelve years of design education for artisans, the issue of copying has emerged among artisan designers. They discuss it furtively, angrily.

As Emma finished her course in Rabari embroidery, she said she felt free of the bonds of perfectionism. It doesn’t have to be perfect! she discovered. Aakib told his Ajrakh student Claire not to fret over a mistake– it will be lost in the beauty of the piece, he said.

As Emma finished her course in Rabari embroidery, she said she felt free of the bonds of perfectionism. It doesn’t have to be perfect! she discovered. Aakib told his Ajrakh student Claire not to fret over a mistake– it will be lost in the beauty of the piece, he said.

Lately I have been writing about Craft as Sustainable Luxury. I love writing, and especially when it involves grappling with concepts, pushing the boundaries, provoking, and coming up with a great new idea.

Lately I have been writing about Craft as Sustainable Luxury. I love writing, and especially when it involves grappling with concepts, pushing the boundaries, provoking, and coming up with a great new idea. Many will be creating for the official opening of Design Craft.

Many will be creating for the official opening of Design Craft.

The Design Course 2016 is over.

The Design Course 2016 is over.

Poonambhai, a weaver from Varnora, graduated from the Somaiya Kala Vidya design course last year. He had actually begun the course in 2013, but at the time of the second session he had an opportunity to go to Delhi for a sale, so he went, saying he would be back in a few days. He missed the whole course and we said he could not continue. He realized he wanted to complete the course, so two years later, at age 40, he came again, starting over from course one.

Poonambhai, a weaver from Varnora, graduated from the Somaiya Kala Vidya design course last year. He had actually begun the course in 2013, but at the time of the second session he had an opportunity to go to Delhi for a sale, so he went, saying he would be back in a few days. He missed the whole course and we said he could not continue. He realized he wanted to complete the course, so two years later, at age 40, he came again, starting over from course one.

In our Outreach program we are teaching our core Design for Artisans course in abbreviated form, tailoring it to the groups and interspersing it with exhibitions to insure income and enthusiasm generation as well as direct implementation of the material. The Bagalkot weavers have taken the colour course and the basic design course, after which they did their second exhibition in Mumbai. Next comes Market Orientation. We had done a field trip to Fabindia and two homes immediately after the Mumbai show. Looking back, the weavers said one home they thought was a museum. The other quickly convinced them that saris could not only be RS 5,000: they could even be RS 50,000!

In our Outreach program we are teaching our core Design for Artisans course in abbreviated form, tailoring it to the groups and interspersing it with exhibitions to insure income and enthusiasm generation as well as direct implementation of the material. The Bagalkot weavers have taken the colour course and the basic design course, after which they did their second exhibition in Mumbai. Next comes Market Orientation. We had done a field trip to Fabindia and two homes immediately after the Mumbai show. Looking back, the weavers said one home they thought was a museum. The other quickly convinced them that saris could not only be RS 5,000: they could even be RS 50,000!