Remembering Hariyaben

Today we interviewed women for the 2018 Design Course at Somaiya Kala Vidya. We have not had a women’s class since 2014, and I remembered Hariyben. It’s been three months since she is gone.

Hariyaben was one of the original trustees of Kala Raksha. I remember having a trustee meeting soon after we founded the organization. An elder man, a brother of her father-in-law, sat himself right in front of us to listen in. I was annoyed and told him that if he sat here, the women would not be free to speak as they have to cover their faces before elder men from their husbands’ families. He left. I felt triumphant. But Hariyaben refused to drink tea. It was some time later that I learned why. “You insulted my relative,” she said. From then I learned many things from her about art, artisans and culture.

Hariyaben was one of the original trustees of Kala Raksha. I remember having a trustee meeting soon after we founded the organization. An elder man, a brother of her father-in-law, sat himself right in front of us to listen in. I was annoyed and told him that if he sat here, the women would not be free to speak as they have to cover their faces before elder men from their husbands’ families. He left. I felt triumphant. But Hariyaben refused to drink tea. It was some time later that I learned why. “You insulted my relative,” she said. From then I learned many things from her about art, artisans and culture.

The first time we went to an exhibition, Hariyaben was one of two artisans who represented Kala Raksha. The exhibition was in Chandigadh. Hariyben’s husband worked with a Sikh living in Kutch. Chandigadh is very dangerous, she informed me. She went nonetheless. We made it through the exhibition safely, and then went to visit the Rock Garden made by Nek Chand. It was a marvelous fantasy of figures made of mosaics of recycled ceramics. Hariyaben was quiet. At the end of the tour, she exhaled and said, “See, I told you it was dangerous!”

What do you mean? I asked.

“Didn’t you see all of those paliyas?!” she exclaimed. (Paliyas are figures commemorating the death of a person.)

Hariyaben was willful. We tussled over tailoring. She was a great, perfecting teacher. She taught many young women to make uncompromisingly beautiful suf embroidery and patchwork. I asked her to assist me in making an interpretation center for traditional embroidery. There, she taught me to understand tradition. We were dressing a mannequin with an embroidered kanchali-kurti. But there was no skirt from the collection to complement the outfit. “What shall we use for the lower garment?” she asked.

Traditional, I answered.

“But which tradition?” she wanted to know. Tradition, she understood, was not static but ongoing.

After working on the exhibition for some time, she told me, “This idea of yours, this exhibition, is not new. We already have it. Every time a women is married she displays her dowry collection for her village– and then her husband’s- to see.

After working on the exhibition for some time, she told me, “This idea of yours, this exhibition, is not new. We already have it. Every time a women is married she displays her dowry collection for her village– and then her husband’s- to see.

We added a library for inspiration. Hariyaben got that before we even installed all of the books. One morning I spied her with a very unusual suf embroidered shawl that she had just finished. It had a huge, complex medallion in the center.

Where did you get that Idea? I asked her.

“From those books you had piled in the office,” she informed me.

When we began the narrative applique project, Hariyaben found a wonderful medium for her imagination. She did an elaborate piece on the first Sharad Utsav festival held in Kutch. She depicted Prakashbhai, me, the Collector and herself in sharply observed detail. And there near the center was the unmistakable then Chief Minister, Narendra Modi. She depicted the Mandvi palace Vijay Vilas, a political meeting, scenes of nature. She illustrated Kutchi proverbs with tongue in cheek humor.

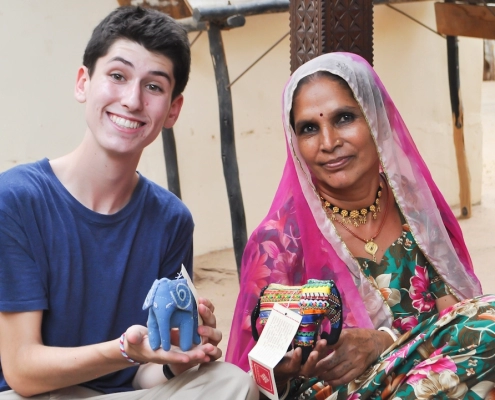

Hariyaben invented wonderfully made toys and dolls, born of her concern over fabric remnants being wasted. She gathered them from the workshop and took them home to fashion camels, elephants and culturally correct figures.

She wanted to start her own individual business, and when we began the Business and Management for Artisans course, she quickly signed up. She knew she was not well. She detected a lump behind her breast bone. I went with her to hospitals in Bhuj and then Ahmedabad, trying unsuccessfully to get a clear diagnosis. It was hard to get a biopsy, and painful. She got fed up and decided to trust in God and take herbal medicine. But she was determined to take the course.

In spite of not being literate, she did well in the course. She made a masterpiece quilt collection. And when she wanted to produce it for an exhibition, she did not give samples for women to copy, but gave them the concept to work out on their own. I wrote about this in an earlier blog, When Women Design.

Hariyaben worked within restrictions. I used to think, if she had been born in another place, another time, what could she have achieved?

I met her a few days before she passed away. She knew she did not have much time left. She was always beautiful, always dignified. Her nails were painted and she was dressed in pink. She asked her daughter Varsha to bring her the dolls they had made. Carefully, she selected the right one, and gave it to me.

I imagine an after life, reincarnation. Maybe, just maybe we will meet again in another time, another place.

For now, I want to remember her by establishing a scholarship for women artisans. She would like that.