A long time ago, there was a chappal maker. His work was good, so I asked him to make some boxes, purses, and bags for Kala Raksha. I sat with him to develop the specifics. They sold. Then he started to sell them through other organizations. I told him he could sell other things elsewhere, but not to sell the designs I had given him.

A long time ago, there was a chappal maker. His work was good, so I asked him to make some boxes, purses, and bags for Kala Raksha. I sat with him to develop the specifics. They sold. Then he started to sell them through other organizations. I told him he could sell other things elsewhere, but not to sell the designs I had given him.

“You didn’t give me designs,” he retorted. “You only gave me ideas.”

At the time I thought there was a misunderstanding. He discounted the value of concept and initiative. He thought that design = prototype.

Recently, I heard a rumor about an artisan who put his work in an online shop. An organization objected, so the rumor goes, saying they had put design development into the product. And finally the artisan was forced to withdraw it from the site. The work was his, I thought, but who had the right to sell it? And who had the right to the profit? So I realized that the issue is more complex and, by now, my perspective has changed.

When I began the journey of design education for artisans, it was largely because I felt that artisans were having their own traditions lifted from them, shaken up, and returned in kits for them to produce. I thought artisans could get more credit for their capability and more pay. In one of the first classes, the men teased an artisan who pinned a concept up on the board. “Did you do that, or did you copy it?” they asked.

When I began the journey of design education for artisans, it was largely because I felt that artisans were having their own traditions lifted from them, shaken up, and returned in kits for them to produce. I thought artisans could get more credit for their capability and more pay. In one of the first classes, the men teased an artisan who pinned a concept up on the board. “Did you do that, or did you copy it?” they asked.

“Copying is what a designer does!” he rejoined. He had seen it for years as designers came to his house and went.

I also hoped that design education would diminish the phenomenon of artisans copying one another. In the traditional context of men’s work, design and ownership were not concepts. (women’s work was a very different story, one for a later discussion) Art existed, and the artisan produced it as best he could. So it is probably not surprising that the same understanding was simply overlayed onto the early innovations. Someone introduced the now ubiquitous “Bhujodi shawl,” and everyone just produced it.

Shyamjibhai, a weaver with the wisdom of experience and an SKV advisor, fully understands how artisans think. “Every year, we do a ‘Donation Design,’” he says. “These are designs based on tradition that are salable, can be done in quantity and are easy to produce. These are designs that we know artisans are going to copy. We do them for a year, and by then so does everyone else.”

Shyamjibhai, a weaver with the wisdom of experience and an SKV advisor, fully understands how artisans think. “Every year, we do a ‘Donation Design,’” he says. “These are designs based on tradition that are salable, can be done in quantity and are easy to produce. These are designs that we know artisans are going to copy. We do them for a year, and by then so does everyone else.”

But his nomenclature reveals the amazingly sophisticated strategy his family has developed in response to the issue in the context of changing times.

“But there are other designs that all weavers can’t do,” he continues, “due to the skill and cost involved. These we keep for our own edge in the market.”

I believed that if artisans develop their design capacity and find their unique voices, diversity will grow, and the need to copy will wane. If each artisan can find his or her own niche, everyone can enjoy good sales. This has, in fact, happened to a great extent, to graduates of the design program.

I believed that if artisans develop their design capacity and find their unique voices, diversity will grow, and the need to copy will wane. If each artisan can find his or her own niche, everyone can enjoy good sales. This has, in fact, happened to a great extent, to graduates of the design program.

However, with the advent of individuality, competition of a different sort is born, and the concept of intellectual property emerges. Perhaps copying is not any more or less than it ever was but now it is easier to identify. And as the stakes become higher, the issues of ownership and copying are becoming more frequent and more thorny.

At the Santa Fe Folk Art Market, a designer happily showed Dayabhai a design he was doing in Kutch, recorded on his mobile phone. Dayabhai was shocked. “It’s my design!” he exclaimed. “I made it for the Co-Creation Squared show in Mumbai, 2013.” Fortunately, the designer recognized the situation, and gave future production to Dayabhai.

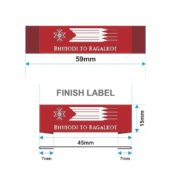

For me, the thrust of design education for artisans has been to enable artisans to be independent designers and entrepreneurs. In the Bhujodi to Bagalkot project a question of ownership came up. The Bhujodi weavers had mentored the designs, and in many cases had given detailed drawings. We had made cloth labels “Bhujodi to Bagalkot” for all of the work to give the show an identity. But each Bagalkot weaver had, on his own, made a paper tag with his name. The tags were identical, except for the name. The weavers felt a tremendous sense of ownership for their work, probably for the first time, as they usually are laborers for a cooperative, and it showed in their engagement as much as in the work.

I had a chance to ask the question during a joint session of the men and women of Somaiya Kala Vidya’s first Business and Management course. The artisans are all earnestly working toward the first exhibition of real Artisan Design- a collective of themed collections- to be held in Mumbai December 3-6. In the session, they were planning the production of the show. They became mired in how to organize the display- by individual? (but there are 12, in a small space!) By craft? Or by product? Before that could be comfortably decided, they moved on to the name of the show. They brainstormed wonderfully, coming up with the name “CRAFT RE-DEFINED” in a way so organic that no one really knows who coined the phrase. But they all knew immediately that that was IT.

Now I got my chance: But what about Somiaya Kala Vidya? I asked. Should the name not be on the show? “Whose products are they, anyway?” I asked.

I saw the group collectively, defensively frown. (Each one had worked so hard to create a logo and a brand identity. Was I going to try to take this away from them?) Finally, one artisan voiced their answer, “They are OURS!”

Good! I answered. But what then is the Somaiya Kala Vidya product?

Without hesitation, Zakiya laughed and pointed to herself. “WE ARE!” she cried.

Ah, yes. So we added the subtitle CRAFT RE-DEFINED: Artisan Designer BMAs from Somaiya Kala Vidya

Everyone wants the opportunity and the satisfaction of creativity… Ownership is critical to enthusiasm and motivation. But it is important to be clear about just what one’s work is.

Everyone wants the opportunity and the satisfaction of creativity… Ownership is critical to enthusiasm and motivation. But it is important to be clear about just what one’s work is.

Thank you, Zakiyaben!

When we last left our brave weavers of Bagalkot, the second round of samples were in process, and we were combing the universe for funding for loans. God is Great, and we managed just what we needed in the time we had. But there were communication challenges and a few doubts, so within days of Dayabhai returning from his highly successful USA tour, he and Nilanjanbhai set out once again for Bagalkot. The mission was to insure that the Bagalkot team was weaving the samples approved, and to make any adjustments necessary to insure that they had the stock they would need for the October exhibition, now just over a month away. Face to face support has no substitute. The weavers were bolstered to finish their collections.

When we last left our brave weavers of Bagalkot, the second round of samples were in process, and we were combing the universe for funding for loans. God is Great, and we managed just what we needed in the time we had. But there were communication challenges and a few doubts, so within days of Dayabhai returning from his highly successful USA tour, he and Nilanjanbhai set out once again for Bagalkot. The mission was to insure that the Bagalkot team was weaving the samples approved, and to make any adjustments necessary to insure that they had the stock they would need for the October exhibition, now just over a month away. Face to face support has no substitute. The weavers were bolstered to finish their collections.

The Somaiya Kala Vidya logo was officially launched with the exhibition of Bhujodi to Bagalkot. Creating this identity was a study in collaboration.

The Somaiya Kala Vidya logo was officially launched with the exhibition of Bhujodi to Bagalkot. Creating this identity was a study in collaboration.