Education for Artisans and Consumers: A Path to Sustainability

Education for Artisans and Consumers: A Path to Sustainability

Judy Frater

Education is almost always the sustainable answer to deep-rooted problems. As the climate crisis looms, over-production and over-consumption contribute to accumulation of waste that critically burdens the environment. A radical shift of focus from quantity to quality is needed to slow the global trajectory toward self-destruction and begin sustainable practices. Value is at the heart of sustainability; people preserve what they cherish. A return to buying better and consuming less can be cultivated by value-centered education.

Hand craft has the potential to lead a movement toward economic, social and cultural as well as environmental sustainability. Traditional hand craft processes use minimal to no fossil fuel energy and produce little to no wastage. Equally important, traditional artisans created for durability and personal meaning.

But in India today, sustainable hand craft livelihoods are threatened by undervaluation. Industrialization of craft has led to over-production, overuse of natural resources, and waste. The push to make craft “affordable” has meant that to maintain even modest livelihoods, artisans must produce in quantity. The fundamental characteristic of hand craft is that it is made by people. There is a human limitation to scale. Each year artisans leave craft because it does not offer adequate income or recognition. Therefore, for craft to remain viable for artisans, it cannot be made cheaper; rather, it must be made more valuable.

A radical shift to focus on values requires cultural adjustment, and thus coordinated education of producers and consumers. My efforts toward this end began with education for artisans of Kutch district in Gujarat. Concerned that commercialization was devaluing craft for the artisans who made it and devaluing artisans themselves, in 2005 I began a year-long program in design education for traditional artisans. The course teaches artisans to recognize and value their cultural heritage and to innovate within its parameters as they define them to reach contemporary markets. A key objective of the educational programs is to encourage individual expression as a path to success alternative to scaled up production. By learning to innovate within traditions, artisans can ensure integrity of cultural heritage. By connecting to contemporary markets, they can gain recognition as well as income.

The experience of 15 years of education for artisans has shown that graduates of the program have clearly increased their incomes as well as their social standing. They have found markets in established companies, with designers, and on online platforms. They have participated in international as well as domestic events. They have received national and international awards and gained recognition in their communities. Graduates have realized several sustainable development goals: no poverty nor hunger, good health and well-being, quality- appropriate- education, decent work and economic growth, and innovation. They are aware of environmental issues and prefer ecologically sustainable practices. And they have built a community of artisan designers.

Because craft traditions are human powered, continuation rests on the next generation of artisans. The most important impact of design education for artisans of Kutch is the return of the next generation from urban jobs and industries to craft as an excellent option for livelihood, rather than a last resort.

Another important outcome of the program is diversification of craft traditions. In 15 years, all graduates have developed clearly recognizable individual styles within their shared traditions, which has expanded markets and extended economic benefits to more individuals. Artisan students love to innovate, and they do so successfully when they know the consumers for whom they are creating.

The domestic market offers a sustainable livelihood to artisans. They can reach it without need for intervention, observe its workings, and learn to innovate appropriately. Yet, despite economic success artisan designers struggle with the contemporary markets to which they have access.

Addressing this challenge begins with understanding craft consumers, and illuminates the fact that sustainable practices require education in values for consumers as well. Crafts Council of England studies in 2010 and 2020 demonstrate that in the UK, ethical consumerism, wellness, and mindfulness are important to craft buyers. People consume craft seeking authenticity, experiences, and ethical and sustainable creation. They choose craft because of its meaning and human connection. Increasingly, motivations for buying craft are more maker-focused. In short, craft consumers want cultural consumption. They value personal connection and individual expression.

The sustainable way to expand the market for craft is not to scale production and consumption, but to educate more people to buy better and consume less. Education of the domestic market in India must bring into focus values of ethical consumerism and mindfulness: concern for the environment and humane working conditions, appreciation of cultural heritage, and value for durability of products and personal connection.

The traditional market for hand craft in India has elements to which we can look to change patterns of consumption. Generations ago, artisans interfaced with traditional clients whom they intimately knew. They focused on creating the best, longest-lasting product for a known and respected user. Clients shared artisans’ standards of evaluation and could see fine variations in how each individual artisan executed a woven dhablo or printed ajrakh. Traditionally, personal recognition and appreciation were exchanged along with payment.

Efforts toward a sustainable craft ecosystem must now focus on a two-pronged education that fosters both excellence and independence of artisans, and cultivates consumer cognizance of the values of craft. In a sustainable craft ecosystem, makers and users must share values centered in cultural heritage, individual interpretation, and durability, and artisans must have direct access to their end users.

The role of the intermediary in this ecosystem is as facilitator and educator. Intermediaries can educate and guide artisans, rather than intercept direct access to clients, and educate consumers to understand the value of craft in terms of issues of environmental, economic, social, and cultural sustainability. The intermediary can reimagine traditional systems of distribution and re-value the personal connection of craft in order to bring genuine sustainability to craft traditions and to the planet.

This article was published by the Center for Environment Education and the Government of India in the book Sustainability in the Handlooms of India

References

Chatterjee, A. (2007), Kala Raksha Vidhyalaya: An Evaluation Report. Sumrasar: Kala Raksha Trust.

Frater, J. and Hawley, J. (2021). ‘Honoring Artisanship over Skilled Labor: The Solution to Sustaining Indian Handloom,’ in Gardetti, M. and Muthu, S. (eds.) Sustainability, Culture and Handloom. New York: Springer

Frater, J. (2019). ‘Education for Artisans: Beginning a Sustainable Future for Craft Traditions,’ in Mignosa, A. and Kotipalli, P. (eds.) A Cultural Economic Analysis of Craft. London: Palgrave.

Klamer, A. (2012). ‘Crafting Culture: The Importance of Craftsmanship for the World of the Arts and the Economy at Large.’ Rotterdam: Erasmus University.

McIntyre, M. H. (2010). ‘Consuming Craft: The Contemporary Craft Market in a Changing Economy.’ London: Crafts Council.

McIntyre, M. H. (2020) ‘The Market for Craft.’ London: The Crafts Council of England and Partners.

Tyabji, L. (2019) ‘Keynote address,’ 3-5 October 2019 5th International Textiles and Costume Congress, Maharaja Sayajirao University, Baroda.

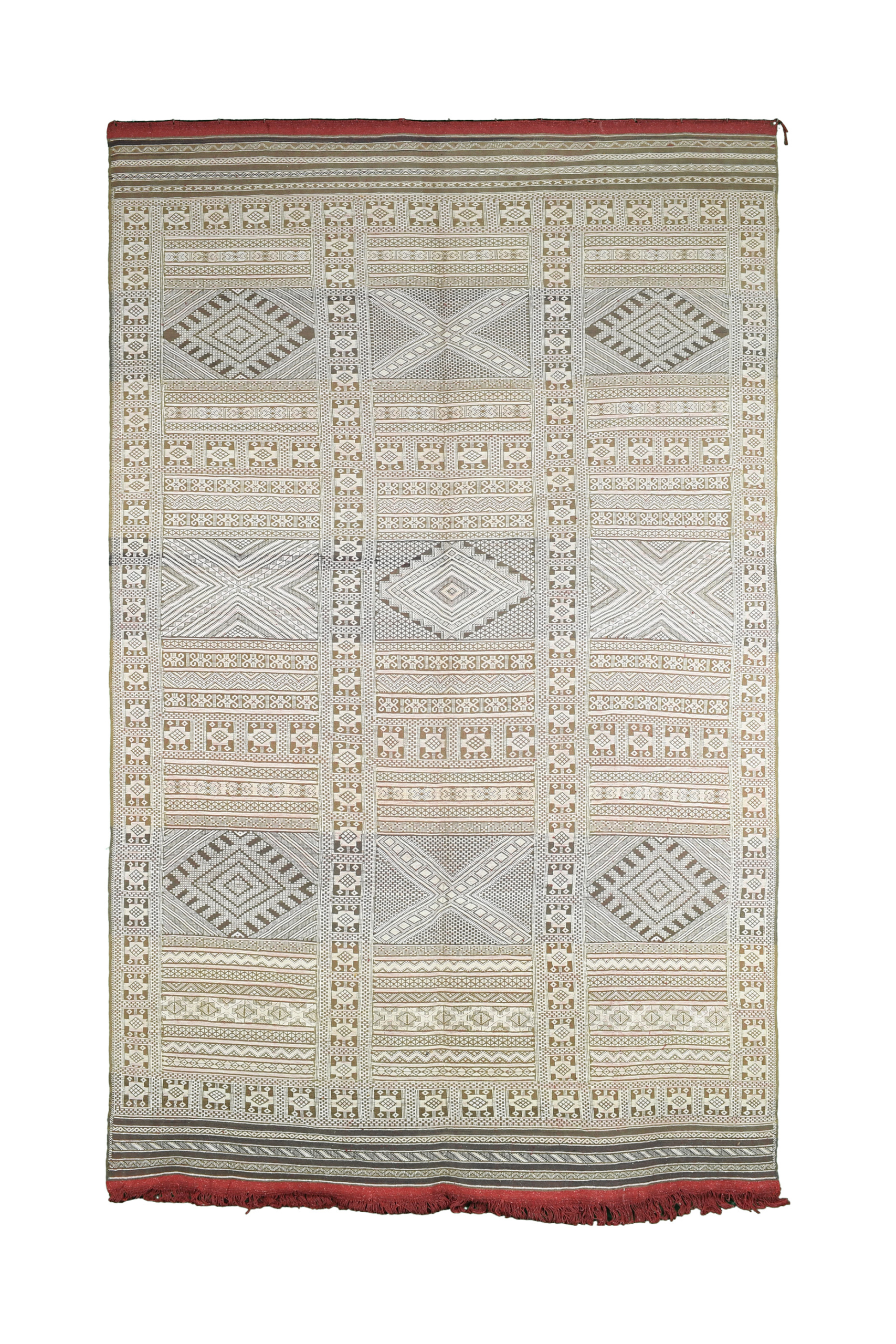

In March 2024, I visited Morocco just for fun, but of course I gravitated to hand craft.

In March 2024, I visited Morocco just for fun, but of course I gravitated to hand craft.

Akib Ibrahim Khatri teaches Ajrakh hand print and natural dye in a Craft Traditions course, Ajrakhpur 2015.

Akib Ibrahim Khatri teaches Ajrakh hand print and natural dye in a Craft Traditions course, Ajrakhpur 2015.

In 2012, the Kala Raksha Vidhyalaya Convocation was sponsored by Tata Power, Adani group and the K.J.Somaiya Trust. Today, Tata and Adani have their own craft CSR projects. The K.J. Somaiya Gujarat Trust now operates the design education program as Somaiya Kala Vidya. What happened between 2012 and now?

In 2012, the Kala Raksha Vidhyalaya Convocation was sponsored by Tata Power, Adani group and the K.J.Somaiya Trust. Today, Tata and Adani have their own craft CSR projects. The K.J. Somaiya Gujarat Trust now operates the design education program as Somaiya Kala Vidya. What happened between 2012 and now?

In the time of the plague in India, 1994, Kala Raksha exhibited a small collection in the National Gallery of Modern Art, Mumbai, and also held a pop-up a few blocks away. A customer contacted me, angry. ‘You are cheating,’ she said. ‘The shawl in the Museum is triple the cost of the one in the pop-up.’ I explained to her that the Museum shawl was yarn dyed in natural dyes and had a lot of fine embroidery, while the pop-up shawl was piece dyed in synthetic dye and had less embroidery of lower quality. Then I added, “If you don’t know the difference, you should buy the cheaper one.”

In the time of the plague in India, 1994, Kala Raksha exhibited a small collection in the National Gallery of Modern Art, Mumbai, and also held a pop-up a few blocks away. A customer contacted me, angry. ‘You are cheating,’ she said. ‘The shawl in the Museum is triple the cost of the one in the pop-up.’ I explained to her that the Museum shawl was yarn dyed in natural dyes and had a lot of fine embroidery, while the pop-up shawl was piece dyed in synthetic dye and had less embroidery of lower quality. Then I added, “If you don’t know the difference, you should buy the cheaper one.”

Today’s craft is created for urban markets. In many regions of India, artisans don’t have direct access to those markets. They are beholden to “Master Artisans” for whom they do job work and who lend them money they won’t repay in their lifetimes, preventing them from leaving their workshops.

Today’s craft is created for urban markets. In many regions of India, artisans don’t have direct access to those markets. They are beholden to “Master Artisans” for whom they do job work and who lend them money they won’t repay in their lifetimes, preventing them from leaving their workshops.

Kala Raksha Vidhyalaya women’s class, 2013.

Kala Raksha Vidhyalaya women’s class, 2013.

Tausifbhai presents his work to family and professional juries during the “Merchandising, Presentation” module of the Somaiya Kala Vidya design course, 2019. Presentation includes an explanation of the collection theme, concept development, and specific innovations the student did, in order to illuminate the thought embedded in the work as well as technical innovations- and create value for the whole of the work: concept and creation.

Tausifbhai presents his work to family and professional juries during the “Merchandising, Presentation” module of the Somaiya Kala Vidya design course, 2019. Presentation includes an explanation of the collection theme, concept development, and specific innovations the student did, in order to illuminate the thought embedded in the work as well as technical innovations- and create value for the whole of the work: concept and creation.

The photo is of the first iteration of the interpretation center of the Kala Raksha Museum. The idea was to portray the traditional context of embroidery for visitors. I engaged artisans to create replicas of pieces in the collection, a prelude to learning to innovate on traditions. I also engaged the late Hariyaben Bhanani, suf embroidery artist, in creating the display to ensure authenticity. A photo of a wedding in her community adds context.

The photo is of the first iteration of the interpretation center of the Kala Raksha Museum. The idea was to portray the traditional context of embroidery for visitors. I engaged artisans to create replicas of pieces in the collection, a prelude to learning to innovate on traditions. I also engaged the late Hariyaben Bhanani, suf embroidery artist, in creating the display to ensure authenticity. A photo of a wedding in her community adds context.