I was honored and humbled to receive the Design Guru award from the Association of Designers of India and JK Lakshmipat University Institute of Design. I was especially honored to be associated with MP Ranjan. Ranjan was a mentor, a friend, and an exemplary design educator. He was a pillar in the development of design education in India.

I am not trained as a designer. And I hope that MP Ranjan, being a challenger of conventional norms, would appreciate this anomaly. Certainly, Ranjan enthusiastically encouraged me when I set out to begin a program of design education for artisans in Kutch. Ranjan’s biography says that his father was an entrepreneur. I recall that he thought of him as an artisan. In any case, Ranjan had great affinity to and respect for artisans.

So, here is my “MP Ranjan Memorial Lecture 2021,” which concerns the evolution of the design education program that today operates as Somaiya Kala Vidya, and how I feel it illustrates Design Education for Recognition.

The idea of design thinking as a particular approach to creatively solving problems- of which I believe MP Ranjan was a proponent- evolved in the late 1950s- early 1960s. It evolved in an academic context, through studies on creativity by highly respected scholars. As such, design was established as a respected discipline.

When design as a distinct discipline was introduced to India at the time of a great focus on industrialization as a key to nation building, designers were encouraged to work with craft traditions, both as a source of distinctly Indian inspiration, and also as a way to “help” traditional artisans adapt to quickly changing markets. Design for craft is often called “Design Intervention.” This approach, unfortunately, resulted in developing a mutually perceived hierarchy, in which design and designers are more valued than craft and artisans.

However, in the words of Professor Ranjan, “Design is a very old human capability that has been forgotten by the mainstream educational systems and the traditionalists alike.”- MP Ranjan 2003

Having studied traditional artisans from an anthropologist’s perspective, I had approached craft traditions with appreciative inquiry.

I could experience the creativity of traditional artisans- and I am distinguishing traditional artisans as those who have learned a hereditary tradition, comprising knowledge and aesthetics as well as skills, from workers who are executing craft techniques. I had studied how traditional artisans appropriately innovated in their traditions in response to changes in their eco-system. Essentially, they successfully followed design briefs.

So I was disturbed by what I felt was devaluing of craft traditions, traditional knowledge, and artisans themselves. I was concerned that this could eventually result in loss of invaluable cultural heritage.

I began Kala Raksha with a traditional artisan family, Prakashbhai and Dayaben Bhanani, and I established the Kala Raksha Museum as an initial experiment in encouraging artisans to innovate within their own traditions for new markets. My objective was to return agency to artisans and enable them to earn more equitably.

I saw recognition of the value of cultural heritage and activating the design capacity inherent in a tradition as key to achieving these goals. So I created the museum as a resource base, and held workshops in which I asked artisans to develop new work inspired by the collections. It took me a long time to realize that was too broad a brief. Years later, Lachhuben, a Rabari embroiderer, confided that when I asked her to create in that context it made her so nervous that she couldn’t eat or sleep!

I learned a lot about design working with traditional artisans.

At Kala Raksha we invited designers and design students to work with artisans. I had the opportunity to observe that the interactions were often not optimum. And, because I knew the artisans, I could observe what didn’t work for them, and how their creative capacity was often not being used. I also had the opportunity to observe how artisans innovated from our museum collections. I started to ponder, what do designers know that artisans do not? And to wonder, what if artisans could learn what designers learn? I thought this might begin to mitigate the power and value differential.

A massive earthquake in Kutch in 2001 was the catalyst that enabled me to consider acting on these ideas. I received an Ashoka Fellowship to develop a curriculum to teach design to traditional artisans in Kutch.

Again, I am not trained in design, though I do have a background, long ago in fine art. So I enlisted experts. I don’t believe anyone can know everything- nor should they. I believe that the approach is to have an idea and be able to find the experts who can help you realize it. So I talked to MP Ranjan and others at NID, and I visited design institutes in the USA. I also enlisted the input of master artisans in Kutch in order to ensure that whatever we taught would support existing traditions. I studied, and through Ashoka I held a curriculum planning workshop at the Rhode Island School of Design. Krishna Patel, NID graduate and faculty, the late Jan Baker, faculty at RISD who had been visiting faculty at NID, the late Chip Morris, and Ashoka Fellow Aleta Margolis were the participants. I would also like to acknowledge the many professional design educators who helped build the program. It is a living, ongoing project.

I launched the program as Kala Raksha Vidhyalaya in 2005. In 2014, I shifted it to the KJ Somaiya Gujarat Trust and we founded Somaiya Kala Vidya, which is the current avatar of the program.

The program has been very successful. One key reason is that I ensured that it was accessible to artisans. Accessible meant thinking in terms of artisans’ situations in terms of time, language, funds and experience. Working traditional artisans must work in order to survive. Their time is precious and limited. Yet, they have very well-developed control of a medium. So the course is one year long, and focused on taking existing knowledge and skills forward. It is structured in intensive 2-week modules. Most artisans can manage two weeks away from work. The link between modules is maintained by homework assignments- those which can be incorporated to support ongoing work. Courses are taught in Gujarati or Hindi. And fees are what is considered “normal” within artisan communities. The program also teaches design through the lens of appreciating tradition, and with hands-on application.

Success of the program further rested on being able to address artisan needs, both as they perceived them and as I did. Here I would like to touch on a basic dilemma of education, and something that I feel the world is grappling with today. The reality is that we often don’t know what we don’t know. So, to me, education is a process requiring mutual recognition and respect. And it requires a delicate balance. Educators need to know what students feel they need, where they are coming from. They need to respect, understand and encourage them. This gives students the license to explore their potential, and to be creative. At the same time, educators need to guide. They provide constraints that encourage development of creativity. Otherwise, we may have a situation such as that to which Lachhuben reacted.

But for guidance to work, students must also recognize and respect their teachers. And, the onus is on educators to earn that respect. I recall one very bright student relating that at first he felt the assignments given were useless. But he did them, and then realized how they benefited him. After that, he said, he decided to try what his teachers asked him to do. Being a student is an act of trust and a leap of faith.

While respecting students and understanding the needs that they perceive, educators must sensitively utilize experience that extends beyond that of students, and provide access to what they feel students also need. So I view education as a kind of co-creation. It is granting permission, while gently exercising guidance based on experience.

Recognition is inherent in the methodology of the course.

It also underpins the objectives. And here is where we zero in on design education for recognition.

In my research on craft traditions, I focused on the roles of craft and the relationships between makers and users. Craft was traditionally personal- artisans and clients knew each other intimately. This connection was what enabled them to successfully innovate. Further, craft was traditionally bartered rather than sold, and personal recognition was a key element in both valuation and satisfaction.

Commercialization- and especially industrialization of craft turned artisans into workers and eliminated any element of personal recognition.

Two aspects comprise recognition: recognition as self-reflection, and external recognition. I founded the program on self-reflection- recognizing tradition as cultural heritage, and a key resource. At the beginning of each year, master artisan advisors begin this process by conducting sessions to present and discuss in depth a range of textiles from their shared traditions.

External recognition is a fruit of the year of hard work. By acknowledging and valuing design thinking as an inherent aspect of craft traditions, and enhancing design thinking with education, the program has equipped graduate artisans to situate themselves in a new ecosystem. Participating successfully in arenas beyond their own society, they have been recognized as creative individuals. This in turn enables artisan designers to value themselves from a broader perspective.

These two aspects of recognition together have worked to build communities.

The ability to apply design thinking created artisan designer leaders, who understand their debts and responsibilities to their traditions, and the value of membership in their communities. They have consciously contributed to the growing success of artisan communities in Kutch. Here I would like to quote a few excerpts from a recently conducted impact assessment of the program.

“In the course we sat with our elders and asked them the history and meaning of motifs. We realized the value of our own work.”~Prakash Naran Siju

“Now we are recognized, and our art is recognized. We may inspire others to not leave our tradition. I tell them to follow my example. If they learn they can grow.” ~Tulsi Puroshottam Puvar

“We show our work to each other, ask feedback. Today we each do different designs. If a customer brings a photo of someone else’s work, we tell them that is his collection and give his address. We are clear. That is the benefit of education.” ~Puroshottam Premji Siju

When artisans first took the course, their goal was primarily to increase income. But after several years, graduates were able to articulate that once basic livelihood was assured, recognition was as important- if not more so- than increased income.

Recognition is an essential human need.

I believe that in learning to successfully apply design thinking, design graduates everywhere gain recognition, along with an appropriate livelihood.

The net result for artisan design graduates is that craft traditions have become a respectable and satisfying profession, building true cultural sustainability.

This is the power of design education.

Artisans, among many people in India, are experiencing extreme stress on their professions due to the prolonged lock down imposed to control the spread of COVID-19. Many people are concerned that Indian craft and handmade face an existential crisis. Baaya Design initiated a group of over 250 designers, members of NGOs and businesses all wanting to help artisans. Suggestions have been made for making new products- with a focus in face masks, for marketing through online platforms and for initiating education in schools. The discussion has been overwhelming. Yet, it is based in certain assumptions that once again bring up questions: who are artisans? and who are craft consumers?

Artisans, among many people in India, are experiencing extreme stress on their professions due to the prolonged lock down imposed to control the spread of COVID-19. Many people are concerned that Indian craft and handmade face an existential crisis. Baaya Design initiated a group of over 250 designers, members of NGOs and businesses all wanting to help artisans. Suggestions have been made for making new products- with a focus in face masks, for marketing through online platforms and for initiating education in schools. The discussion has been overwhelming. Yet, it is based in certain assumptions that once again bring up questions: who are artisans? and who are craft consumers? The lock down imposed on 24 March 2020 has severely impacted artisans in Kutch. “After the earthquake of 2001, Kutch was devastated,” Irfanbhai notes. “Now it is the whole world. Everyone’s income is stopped, while expenses are continuing. Everyone has the same problem. Our production and sales are both blocked. Some of our orders, which would have been finished in 4 or 5 days have been cancelled. Other customers want our stock, but we can’t send it because transport is shut down. The artisans who work for us are in a bad situation. They are daily wage earners who live in nearby villages. It is Ramzan and we want to distribute alms. We made ration kits and distributed them.”

The lock down imposed on 24 March 2020 has severely impacted artisans in Kutch. “After the earthquake of 2001, Kutch was devastated,” Irfanbhai notes. “Now it is the whole world. Everyone’s income is stopped, while expenses are continuing. Everyone has the same problem. Our production and sales are both blocked. Some of our orders, which would have been finished in 4 or 5 days have been cancelled. Other customers want our stock, but we can’t send it because transport is shut down. The artisans who work for us are in a bad situation. They are daily wage earners who live in nearby villages. It is Ramzan and we want to distribute alms. We made ration kits and distributed them.”

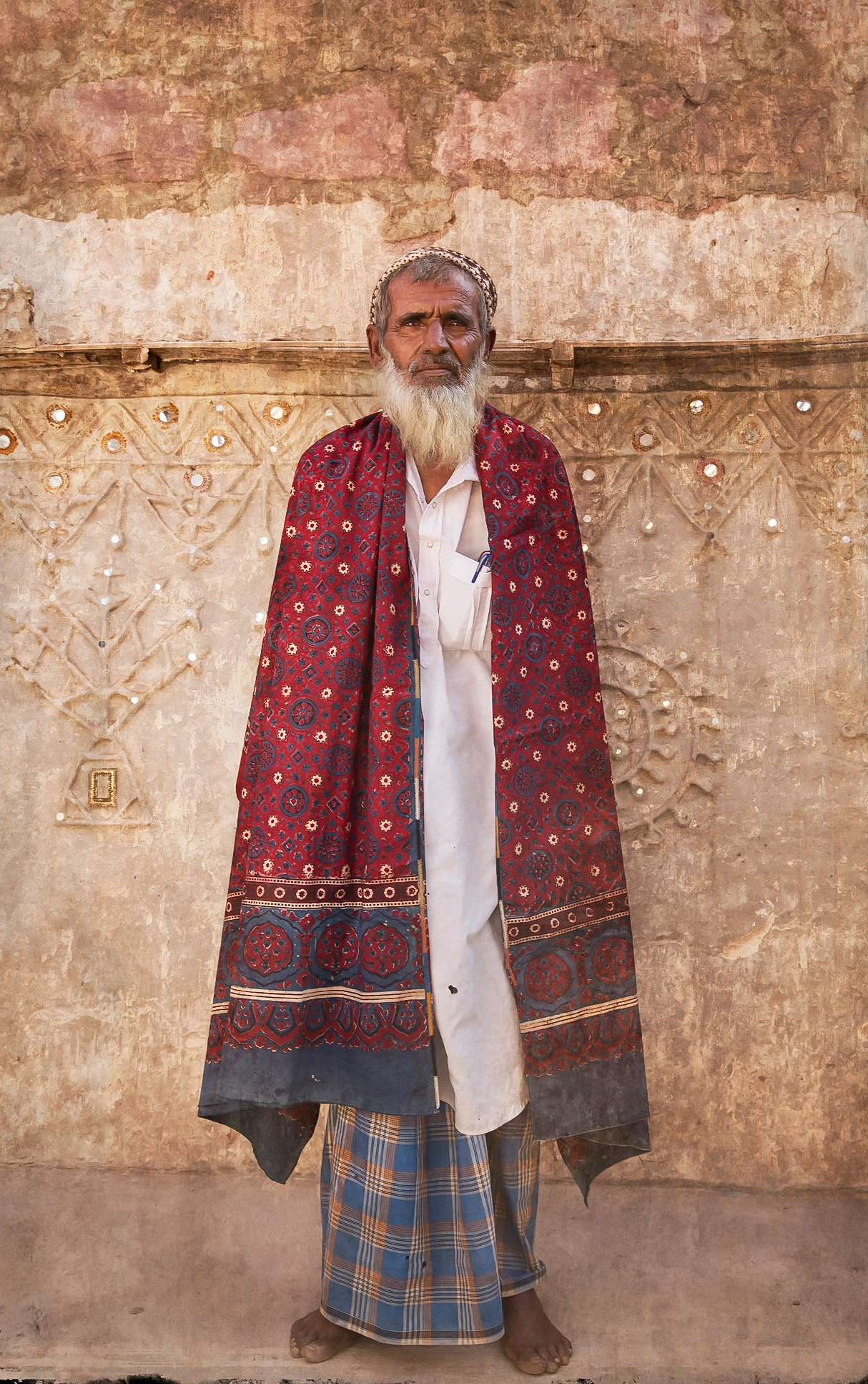

Dr. Ismail Khatri, a 9th generation Ajrakh printer who has an honorary PhD from De Montfort University, UK, is retired to research and development these days. His two sons are busy printing vast quantities of fabric for clients all over the world. So Ismailbhai is going slow. He recently carved a whole set of blocks for a traditional Malir, a fabric originally from the town of Malir in Sindh, which Maldhari pastoralists wore as a sarong. He had always thought that one of the border motifs, a spade, was odd. Who played cards back then? While slowly carving, he had a vision: the motif was originally a mud pot similarly shaped. So he carved the block from his vision. And he printed and dyed the Malir himself. The textile is luminous with life- a world away from the wonderful array of printed textiles in his shop.

Dr. Ismail Khatri, a 9th generation Ajrakh printer who has an honorary PhD from De Montfort University, UK, is retired to research and development these days. His two sons are busy printing vast quantities of fabric for clients all over the world. So Ismailbhai is going slow. He recently carved a whole set of blocks for a traditional Malir, a fabric originally from the town of Malir in Sindh, which Maldhari pastoralists wore as a sarong. He had always thought that one of the border motifs, a spade, was odd. Who played cards back then? While slowly carving, he had a vision: the motif was originally a mud pot similarly shaped. So he carved the block from his vision. And he printed and dyed the Malir himself. The textile is luminous with life- a world away from the wonderful array of printed textiles in his shop. Many traditional textiles, such as the Malir, are all but forgotten. We hold our “Masters” program every year so that the next generation of artisans can draw from their rich traditions.

Many traditional textiles, such as the Malir, are all but forgotten. We hold our “Masters” program every year so that the next generation of artisans can draw from their rich traditions. In a world now concerned with sustainability, what is equally important to learn from the Masters is a model for genuine sustainability. Sustainable Fashion is an oxymoron: it cannot exist. Fashion by nature changes, and the fashion industry by nature wants us to keep consuming so that it is sustained.

In a world now concerned with sustainability, what is equally important to learn from the Masters is a model for genuine sustainability. Sustainable Fashion is an oxymoron: it cannot exist. Fashion by nature changes, and the fashion industry by nature wants us to keep consuming so that it is sustained.

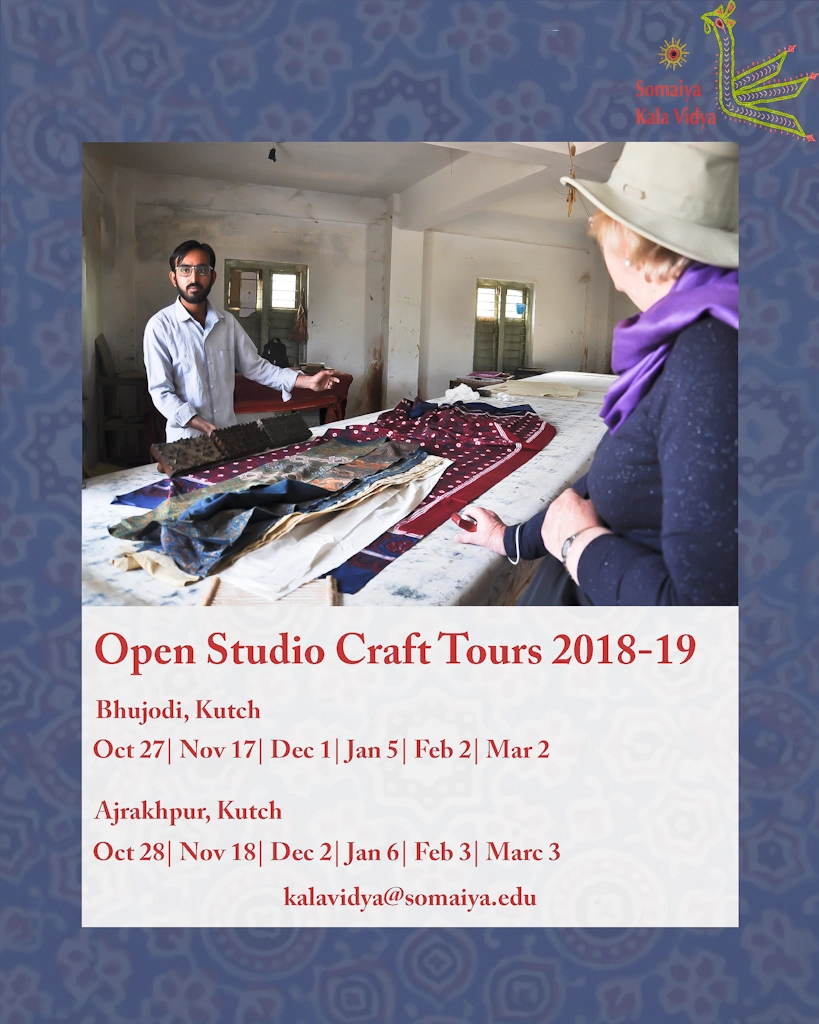

Last year, Somaiya Kala Vidya began Open Studio Tours. The idea is borrowed from the western world, where artist/craftspeople live in a niche and invite people to visit their studios on designated days. It is a mutually beneficial idea: people have the chance to interact with artists, see their work and take home more than a product- an experience. For the artists it means not being annoyed by interruptions to their work, but being ready for visitors and in a mood to welcome them. Win-win.

Last year, Somaiya Kala Vidya began Open Studio Tours. The idea is borrowed from the western world, where artist/craftspeople live in a niche and invite people to visit their studios on designated days. It is a mutually beneficial idea: people have the chance to interact with artists, see their work and take home more than a product- an experience. For the artists it means not being annoyed by interruptions to their work, but being ready for visitors and in a mood to welcome them. Win-win.

In April, Somaiya Kala Vidya began an Outreach project with Avani Kumaon. Avani, a nearly self-sufficient voluntary organization, is situated deep in the Kumaon Hills. The nearest village is Tripura Devi. A 7-hour arduously winding road journey is inevitable, whether you take the train to Kathgodham or the flight to Pantnagar.

In April, Somaiya Kala Vidya began an Outreach project with Avani Kumaon. Avani, a nearly self-sufficient voluntary organization, is situated deep in the Kumaon Hills. The nearest village is Tripura Devi. A 7-hour arduously winding road journey is inevitable, whether you take the train to Kathgodham or the flight to Pantnagar.

We have a steady stream of visitors who make the pilgrimage to Adipur because they are concerned with craft. Concern is vital. Yet I can’t help asking a nagging question: Why Craft? What is the concern?

We have a steady stream of visitors who make the pilgrimage to Adipur because they are concerned with craft. Concern is vital. Yet I can’t help asking a nagging question: Why Craft? What is the concern?