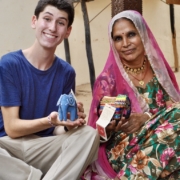

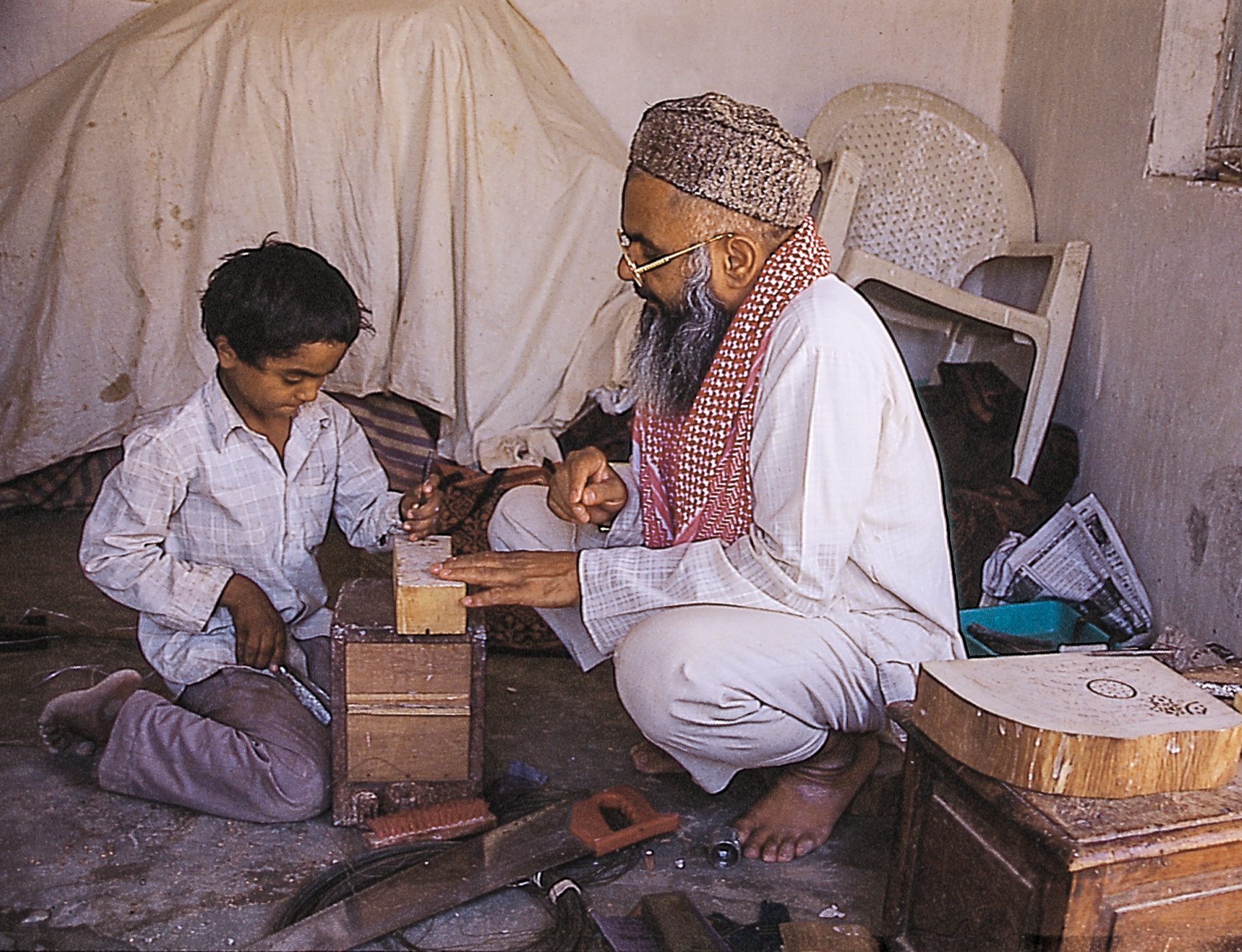

The late Hariyaben Bhanani explains the toys she designed and created to an American student. Hariyaben couldn’t bear to see scraps of painstakingly embroidered fabric thrown away, so she rescued them, took them home, and painstakingly patched them together to form elephants, camels and dolls that she stuffed with other fabric remnants. She lived the spirit of sustainability.

The late Hariyaben Bhanani explains the toys she designed and created to an American student. Hariyaben couldn’t bear to see scraps of painstakingly embroidered fabric thrown away, so she rescued them, took them home, and painstakingly patched them together to form elephants, camels and dolls that she stuffed with other fabric remnants. She lived the spirit of sustainability.

In her novel Flight Behavior, Barbara Kingsolver brilliantly illuminates the climate crisis through a discussion between her Appalachian protagonist and an environmental activist. ‘Bring your own containers to restaurants for leftovers,’ the activist says, ‘and minimize air travel.’ Dellarobia hasn’t eaten in a restaurant for 2 years and has never been on a plane. Nor does she drink bottled water, or have disposable income to invest in social responsibility.

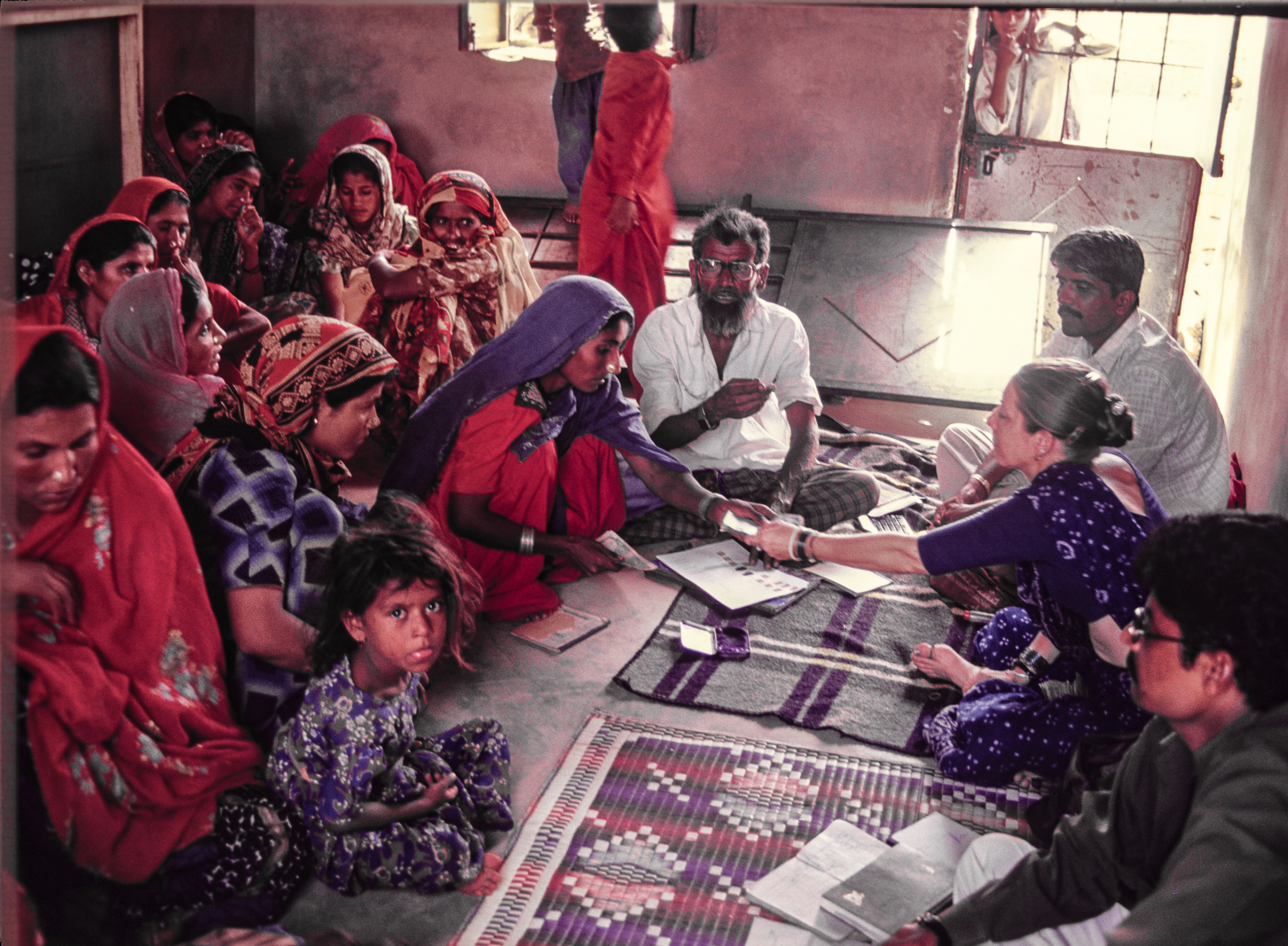

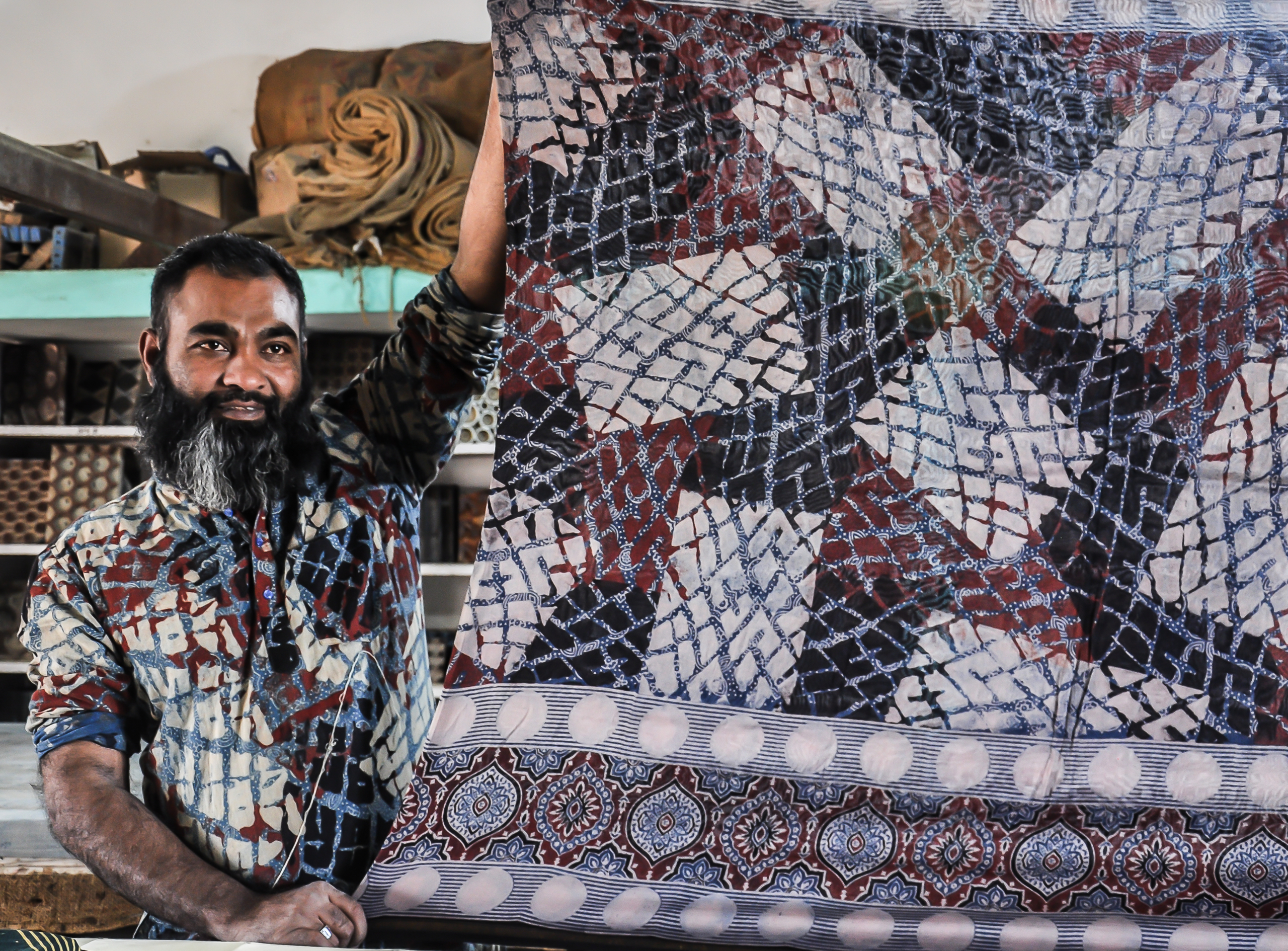

The 99% have contributed minimally to the environmental crisis. Artisans of Kutch in fact live astonishingly eco-friendly lives. Designers of au courant sustainable fashion who come to Kutch villages seeking textile waste to up-cycle are routinely turned away empty handed. Original scale traditional textiles of Kutch were rooted in sustainability. Weavers used any residual yarn in finishing, or in the next textile. Ajrakh and batik printers recycled resist substances, and exhausted natural dyes. Village women stitched garments with no-waste patterns. None of these textiles used fossil fuel energy. Scaled up production today trades some of these principles for speed and income. Still, environmentally sound grounding is a good reason to use hand crafted products.

But even more valuable in becoming environmentally responsible is understanding the ethos of hand craft. If we slow down to hand craft speed, we can observe why artisans work as they do. Vasant Rao meticulously collects the gold dust from a gold pendant he filed to perfection. Shakilbhai salvages the wax from today’s batik to use tomorrow. Hariyaben collects the textile cuttings from the tailoring room and fashions delightful animal toys. In the local craft ecosystem described earlier, value was the basis of traditional design and creation. Artisans did not waste because they valued materials, their own skills and efforts, and their consumers.

The most basic tenet of conservation is that you preserve what you value. We can learn more than craft skills from traditional artisans. Can we engage them as teachers in early education and invite them to share world views as well as technology?

August 12, 2023

August 12, 2023

August 5, 2023

August 5, 2023

July 29, 2023

July 29, 2023

July 22, 2023

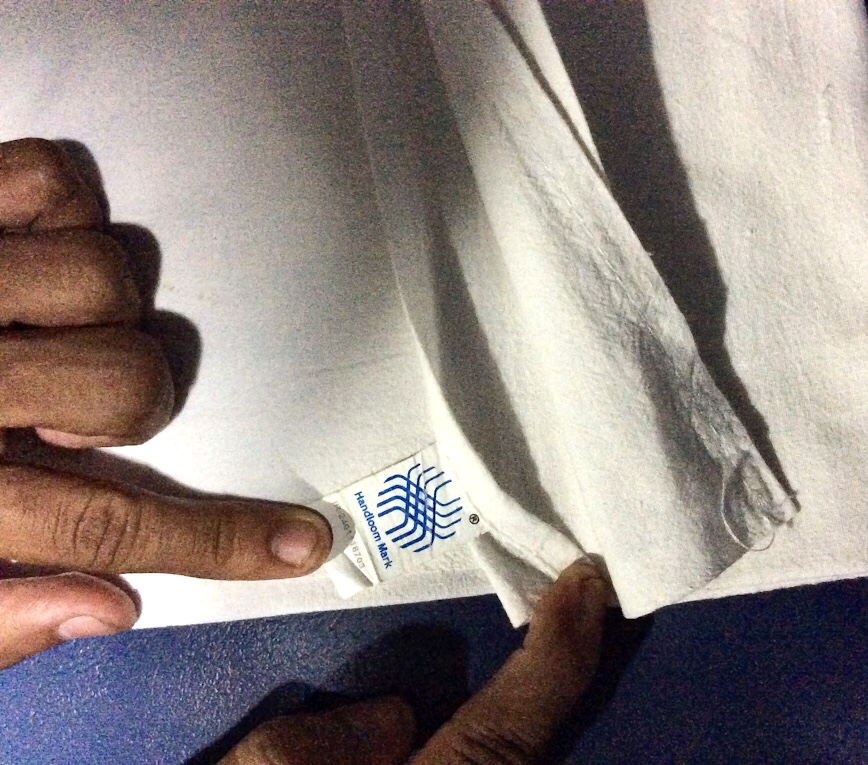

July 22, 2023 What’s wrong with these pictures? The last handloom weaver in a small Karnataka village weaves plain white yardage for school uniforms; a poly-cotton railway sheet proudly displays the handloom label.

What’s wrong with these pictures? The last handloom weaver in a small Karnataka village weaves plain white yardage for school uniforms; a poly-cotton railway sheet proudly displays the handloom label.

July 8, 2023

July 8, 2023

July 1, 2023

July 1, 2023

June 24 2023

June 24 2023

June 17, 2023

June 17, 2023

June 10, 2023

June 10, 2023