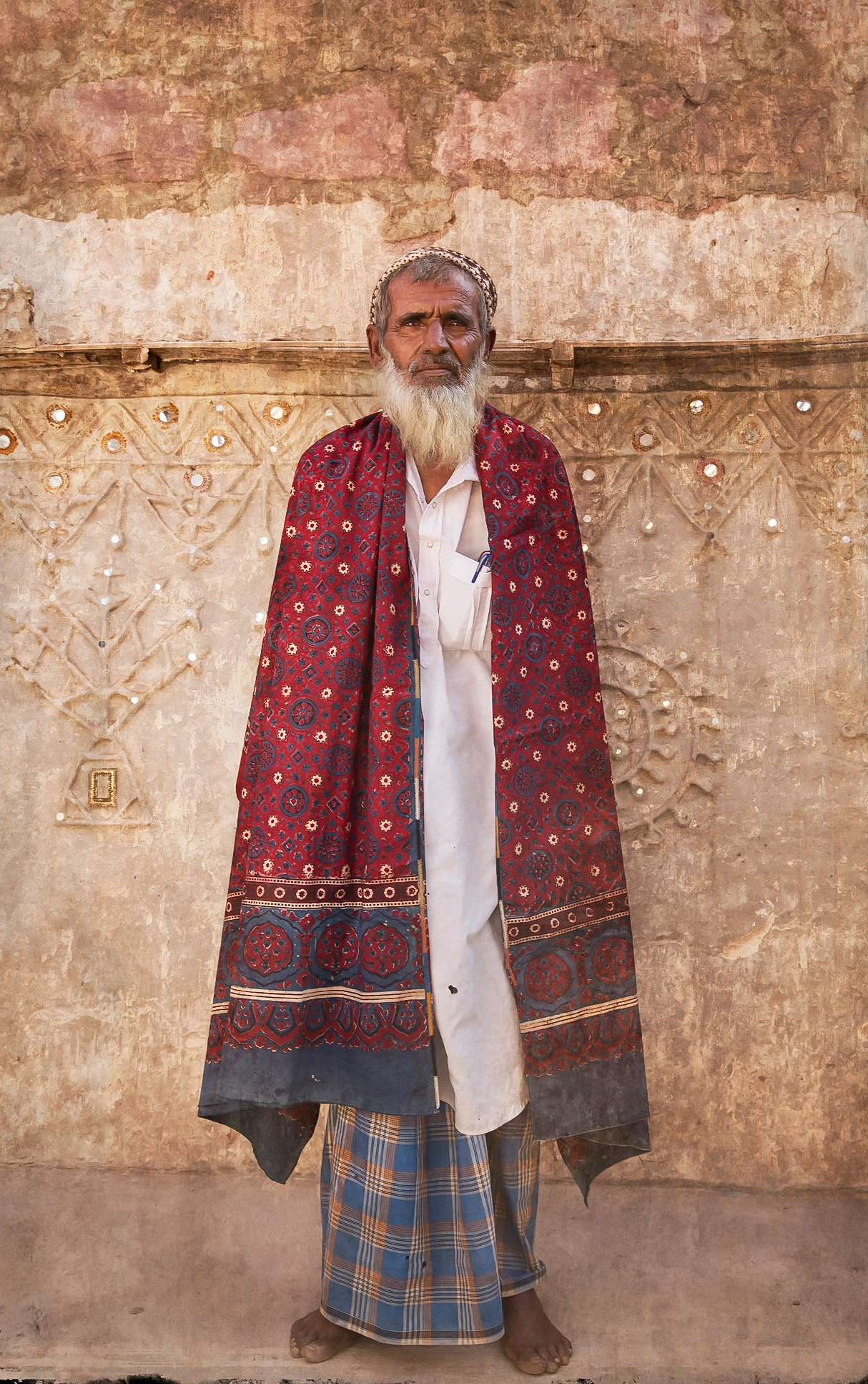

Dr. Ismail Khatri, a 9th generation Ajrakh printer who has an honorary PhD from De Montfort University, UK, is retired to research and development these days. His two sons are busy printing vast quantities of fabric for clients all over the world. So Ismailbhai is going slow. He recently carved a whole set of blocks for a traditional Malir, a fabric originally from the town of Malir in Sindh, which Maldhari pastoralists wore as a sarong. He had always thought that one of the border motifs, a spade, was odd. Who played cards back then? While slowly carving, he had a vision: the motif was originally a mud pot similarly shaped. So he carved the block from his vision. And he printed and dyed the Malir himself. The textile is luminous with life- a world away from the wonderful array of printed textiles in his shop.

Dr. Ismail Khatri, a 9th generation Ajrakh printer who has an honorary PhD from De Montfort University, UK, is retired to research and development these days. His two sons are busy printing vast quantities of fabric for clients all over the world. So Ismailbhai is going slow. He recently carved a whole set of blocks for a traditional Malir, a fabric originally from the town of Malir in Sindh, which Maldhari pastoralists wore as a sarong. He had always thought that one of the border motifs, a spade, was odd. Who played cards back then? While slowly carving, he had a vision: the motif was originally a mud pot similarly shaped. So he carved the block from his vision. And he printed and dyed the Malir himself. The textile is luminous with life- a world away from the wonderful array of printed textiles in his shop.

What do we have to do to get THIS quality? I asked him.

He laughed. “You have to make it with love,” he said.

Weeks later, Dr. Ismail and the other master artisan advisors for our design education for artisans program came to discuss tradition with the current students. Ismailbhai related how, while he was carving the blocks for the Malir, he realized that the fabric told the story of the Maldharis who wore it. One motif shows the wind, another shows a stepwell. The herders must always keep wind and water for their herds in mind. Then there is the water pot- not just for storing water, but it was also used as a flotation device when crossing a river. The herder put his Malir or Ajrakh in it to keep dry, and floated easily to the other side. One motif is called “ladu,” the name of a sweet. But when Ismailbhai was deciphering the theme of pastoralism he realized it has another meaning- the rolled up reed mats. The mats are stretched around a simple frame to make a home, and when it is time to move on, they are rolled up. The motif is a cross section of the roll! Reading the motifs, Ismailbhai related the rich nuanced life of his original clients, never seen by the students of 2019.

One weaver, fascinated, said that this amazed him- and that he felt dispossessed: he had never had his traditional weavings “read” to him this way. He automatically treasured the Malir, and realized the importance of stories in bringing work alive.

Today, hand block printed fabric is produced in thousands of meters, racing to keep pace with the industrial production that forced it to seek markets beyond the traditional consumers.

Many traditional textiles, such as the Malir, are all but forgotten. We hold our “Masters” program every year so that the next generation of artisans can draw from their rich traditions.

Many traditional textiles, such as the Malir, are all but forgotten. We hold our “Masters” program every year so that the next generation of artisans can draw from their rich traditions.

In a world now concerned with sustainability, what is equally important to learn from the Masters is a model for genuine sustainability. Sustainable Fashion is an oxymoron: it cannot exist. Fashion by nature changes, and the fashion industry by nature wants us to keep consuming so that it is sustained.

In a world now concerned with sustainability, what is equally important to learn from the Masters is a model for genuine sustainability. Sustainable Fashion is an oxymoron: it cannot exist. Fashion by nature changes, and the fashion industry by nature wants us to keep consuming so that it is sustained.

Striking in the traditional system of hand printed, natural dyed textiles of Kutch, is that highly sophisticated, technically complex, and exquisitely beautiful textiles were created for simple, poor pastoralists and agriculturists. They had only one or two of each textile- one to wear while the other was being washed. But they were of what today would be understood as museum quality– and should be considered as luxury items. The quality was always as good as possible because the maker and consumer knew each other intimately, and both equally understood and appreciated the quality of fabric, printing and dyeing. There was satisfaction in making and consuming and no thought to cut corners in quality.

Village people knew precisely how to buy less and buy better. Their textiles were made to last a long time and were never thought of as expensive. They were worth the price, and that was exchanged in barter. When I asked Irfanbhai Khatri how they insured that the exchange of textiles and milk, goats or grains was equal, he answered simply, “We didn’t.” Everyone got what he needed.

We probably can’t go back to a barter system now. But can we learn from the system in which maker and consumer share an understanding of quality? Can we think of buying less and buying better? Can we consider personal expression of style rather than commercially dictated fashion? And can we imagine cherishing, purchasing from an artisan so that, in the words of weaver Vishramji Valji, “As it slowly wears away you remember the person who made it.”

All this requires a focus on the human connection that was the basis of the traditional system- making and using textiles with love.