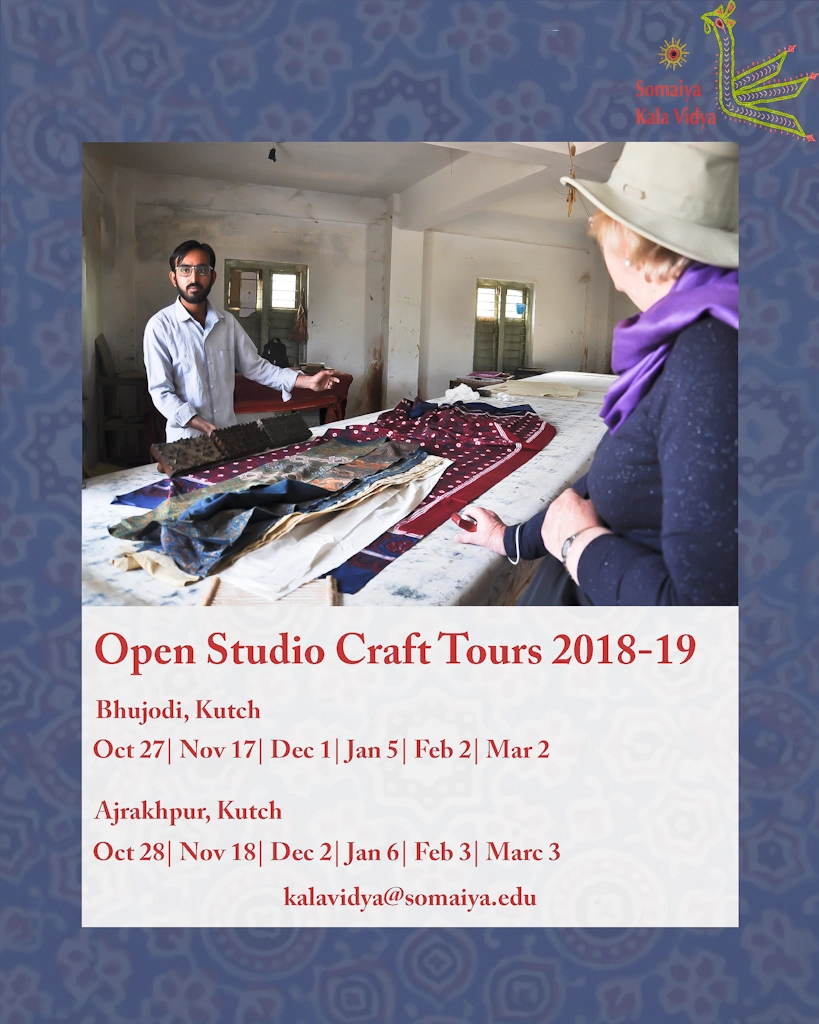

Last year, Somaiya Kala Vidya began Open Studio Tours. The idea is borrowed from the western world, where artist/craftspeople live in a niche and invite people to visit their studios on designated days. It is a mutually beneficial idea: people have the chance to interact with artists, see their work and take home more than a product- an experience. For the artists it means not being annoyed by interruptions to their work, but being ready for visitors and in a mood to welcome them. Win-win.

Last year, Somaiya Kala Vidya began Open Studio Tours. The idea is borrowed from the western world, where artist/craftspeople live in a niche and invite people to visit their studios on designated days. It is a mutually beneficial idea: people have the chance to interact with artists, see their work and take home more than a product- an experience. For the artists it means not being annoyed by interruptions to their work, but being ready for visitors and in a mood to welcome them. Win-win.

We had an additional goal. We wanted some of the talented artisan design graduates to be known, and to have the opportunity to learn from interacting with clients. In Kutch, as in most tourist places, a few people become well known, and all of the tourists go to them. The artisans benefit in many ways. But after a while tourists also feel that they are going to well-traveled destinations, and seek fresh experiences. So we hoped on this front to be win-win too.

After the first season, Kuldip Gadhvi, a local tour professional working with us on this project, and I met with thirteen Artisan Designers to see what their experiences were. Sitting in an orchard, shaded by huge mango trees, we asked how they thought the pilot year had gone.

No one volunteered.

Uh oh, I thought. After some silence, I asked if they could begin with the goals we originally had?

Finally, they began to talk.

The goal was grand, Ifranbhai recalled. We wanted to begin working toward what would eventually lead to a major event- an exhibition that would draw people to Kutch like the Santa Fe International Folk Art Market. It should become a go-to event.

So, how did we do this first year?

Khalidbhai Usman offered that if we want to attract good visitors, artisan designers need to bring only their exclusive work to the exhibition at the end of the tour. They should bring their own new designs, work visitors don’t otherwise get to see- not the work available everywhere. If the work is new and interesting, people will come, he said.

I asked if they were they concerned that if they show their new work, it will be copied? They all agreed that copying was a universal issue. Designs will be copied, by artisans who are not graduates- and anyone using the internet. But copying within the group was not an issue, they assured.

Soyabbhai said that bringing ordinary work also makes a difference in pricing. Ordinary work is cheap- making new work seem expensive.

Khalidbhai shared that in Ajrakhpur, the group has decided to meet the day before the Open Studio Tour, jury the work, and then only display new work. They will also keep a record of who participated, and what the results were. And they will have all of the sales go through a central billing person so that it’s easy to tally.

Soyabbhai suggested that if there is a small group, they should select just a few artisans. I reminded them that they had decided that for each tour there would be only a few demonstrators, but the exhibition and sale at the end would be open to all who are interested. Junedbhai and Prakashbhai have thought of selecting the hosts for each tour based on proximity, so the visitors don’t have to walk a lot. Khalidbhai added that in Ajrakhpur they also make sure to clean up the area that will be highlighted in a tour.

But how much work should we bring for the exhibition? Niteshbhai wanted to know. When someone brings a huge pile, it eclipses those with less work. They discussed this at length, and agreed to keep a limited number of pieces per person, but no one could bring himself to determine that number.

Product segued into display. The Ajrakh artisans thought it was a good idea to display by product rather than person. But Aslambhai disagreed. Display by person is better, he said, because each artisan’s collection would be clearly understood. His experience at his BMA exhibition was that when there was a crowd it sometimes became hard to get through it in time to reach an interested customer and explain his work. Other artisans felt that they all know each others’ work and anyone nearby can explain someone else’s collection. When we were in class, they said, we heard each other’s presentations so often we could repeat them by heart. Niteshbhai summed up: they should display as a group, and agree to help each other. Junedbhai concluded with the thought that the method of display could relate to the size of the group.

Juned also pointed out that the tours aren’t only about sales; there is explanation and interaction with guests, which generates increased visibility.

“–Especially for those artisans who don’t have a shop,” Pavanbhai added. Plus the tours offer artisans a chance to share information within the group. “We don’t go to each other’s homes without any reason,” he explained. The Open Studios provide an opportunity to meet and see what’s going on.

Prakashbhai agreed, this is an opportunity for our work to get into visitors’ sights and hearts.

Pachanbhai said he thought the tours were an opportunity for planning. “Even if it’s short notice, it gives us a chance to plan,” he said. “Plus, people begin to understand that each of us has a unique style. Sometimes the visitors keep in touch with us afterwards.”

Kuldipbhai agreed, “The Open Studios can be an opportunity to explain your design work, your USP. Live discussion is important for visitors. And let’s understand them as visitors rather than clients. If they want to just buy a product, they can do it online.”

True, echoed Pavanbhai. When buyers come to my shop, they bargain. In these tours, no one has bargained.

Khalilbhai had been quietly listening for the whole meeting. Finally he gathered the courage to speak. “What if you know what to say, but don’t have the ability to communicate?” he asked

This struck a chord. A major concern is how to market oneself?

Aslam related, “In an exhibition I can speak to anyone. But somehow among my friends I feel shy.”

“Your work is excellent and exceptional,” Kuldipbhai told them. “Now if you can bring it to life, it adds value.”

“Speak in Gujarati or Kutchi!” I said. “But speak. People want to communicate with you. And there is a difference between having Kuldipbhai speak for you, and you speaking and with his translation: the difference is contact.”

“Craft is the language of the heart,” Jentibhai said.

Finally, Prakashbhai requested that they find a way to determine who will participate in each tour. “Those who are genuinely interested should volunteer,” he said, “and also help organize, so that there is no scrambling at the last minute.”

It’s a matter of prioritizing, I noted.

“We need to be into it,” Junedbhai said.

Khalidbhai concurred. “We need to make a commitment, make this event as important as the Santa Fe Folk Art Market, so that our goal will come true.”

Listening to the discussion, I realized that it was about more than our Open Studio Tours; it was about Artisan Designers and their market.

The tours provide learning for visitors. (“It is totally jaw dropping to be educated on the complexity of Ajrakh printing and weaving techniques of Bhujodi- and all of the innovations!”) As we had hoped, the tours also provide learning for artisans. In one season, Artisan Designers have learned about being responsible, working together, and managing this project. They are taking ownership. They are thinking of the visitor’s experience. They are learning to overcome barriers of inhibitions and communicate.

Building local respect builds self-respect. Exposure has provided an opportunity to move toward the ability to reach appropriate markets effectively- in a low-stress situation that allows open exploration, exchange.

Open Studio Tours are not just about purchase, as Kuldipbhai and Pavanbhai said. They are a human exchange, rather than a commercial one. So when someone purchases, it is an experience rather than a product. This is why the Santa Fe International Folk Art Market works. So perhaps we are beginning a microscopic version of that phenomenal event.

What the Artisan Designers learned will surely make our Open Studio Tours even better this year… and it will develop their enterprises.

Win-win.

In April, Somaiya Kala Vidya began an Outreach project with Avani Kumaon. Avani, a nearly self-sufficient voluntary organization, is situated deep in the Kumaon Hills. The nearest village is Tripura Devi. A 7-hour arduously winding road journey is inevitable, whether you take the train to Kathgodham or the flight to Pantnagar.

In April, Somaiya Kala Vidya began an Outreach project with Avani Kumaon. Avani, a nearly self-sufficient voluntary organization, is situated deep in the Kumaon Hills. The nearest village is Tripura Devi. A 7-hour arduously winding road journey is inevitable, whether you take the train to Kathgodham or the flight to Pantnagar.